Writing in the dark

In search of the moon

I’ve always thought of summer as somewhat surreal – a departure from reality of sorts. Cities empty out like a De Chirico painting, and we find ourselves in places that are far from home. No one is really reading their emails, so if you’ve opened this, here’s something a little different for you. I’m afraid it’s not about drinks or music this time, but it is about something else which is central to this newsletter and underlies everything: writing. We’ll be back soon with something that feels a little closer to home. Enjoy the sunshine in the meantime.

We are standing at the edge of the shore. No moon in sight, the sky wrapped in bruise-red storm clouds. The only other signs of life are the eerie green lights of the fishing boats, bobbing on the black sea, but I doubt anyone is actually on them. Out here, there are no cafés or bars, no hotels, no people. Just a long, empty beach that eventually leads into the wilderness.

We came out in search of phosphorescent plankton, hoping to see the tide sparkling like a net of fine blue jewels. Following a path through the jungle, we came to this secluded beach, where the darkness is rich and unpolluted. But the clouds gathered with a pace, and here we are, far from the village at the edge of a storm.

Now, without a sound, the sky erupts in a brilliant flash of lilac. Four forks of lightning. Four bolts of bright, hot, unearthly silver ripping through the atmosphere. The sight of it is incredible, in the most literal sense of the word. For a moment, I forget to breathe. The light show continues like this in a spectacular pattern. Black, lilac, silver, black. Colossal eruptions of energy. Electric lines writing themselves across the sky, one dazzling split second at a time.

To say it is beautiful is meaningless. It makes it sound both trite and false, a statement devoid of meaning. What do we mean by beautiful anyway? Beauty is sanitising. It reduces the complexity of the thing described, files its edges into a palatable shape. But this is terrifying and strange. Burke might have described it as sublime, but that too has lost its edge. So I will try to explain it another way. It is disorienting. Imagine moving around a pitch-black room in your own home, and just for a split second, someone switches the lights on. In that brief instant, you see that things are not where you thought they were. Certain objects, dull by the light of day, now seem to shine with their own life force. The whole character of the house has changed, as if its truer nature has been revealed. But then the lights go off, and in the end, the darkness is familiar, comforting even. This is what it feels like to look at a landscape illuminated by lightning.

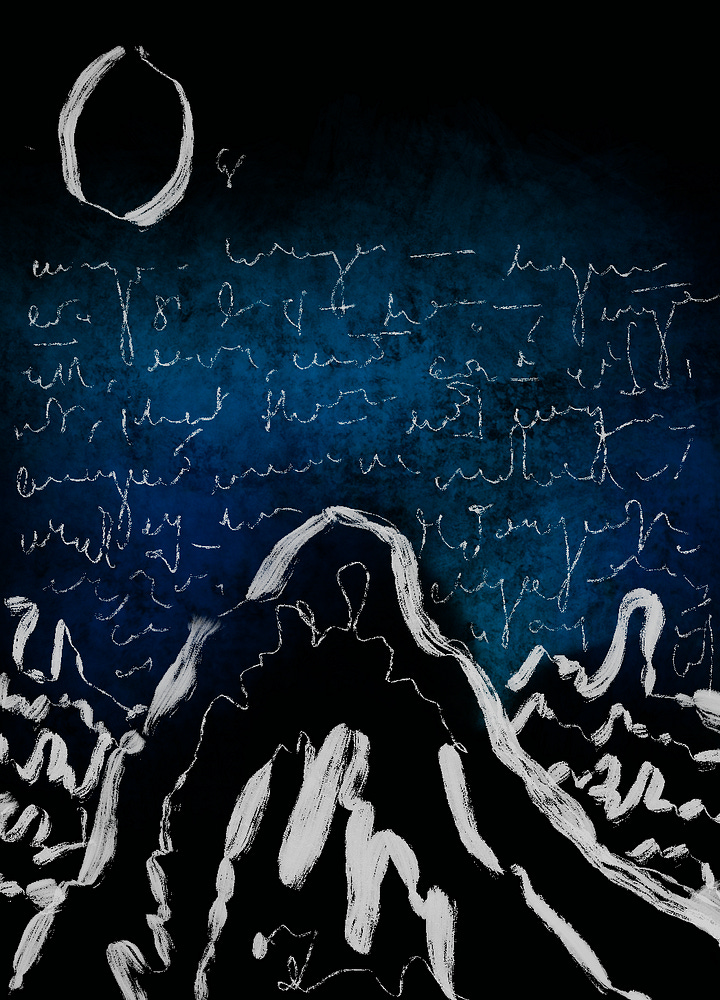

Experiences of extreme natural phenomena – whether you call it the sublime, the sacred or the meteorological – are powerful. They have inspired artists, writers and theologians for millennia. Like many before me, I find myself wanting to capture the moment, to render it into something concrete that can be held up to the light. Photography is useless, so instead, I take out my notebook and attempt to fix it in words. I stand in the sea, looking into the dark, waiting for the lightning. Between these flashes, I write whatever words come into my mind. Animal, reflection, danger, scared. When I look up, I am alone in the dark, and my heart beats faster. I am convinced there are strange shadows behind me. Being here is a risk, but somehow it feels like an important part of the process.

This is the first time I have done such an exercise. Afterwards, sitting in a restaurant in the village, while the storm rages overhead, I open my notebook to see that what I’ve written are barely words. They are nothing like my usual handwriting – loose, misshapen marks slipping down the page, ballooning outwards, collapsing in on themselves. Lines of ink that will mean very little to anyone but me.

When we are talking about marks on a page, what is the difference between writing and drawing? The assumption of meaning, perhaps. If I draw a straight line, it has no fixed meaning, but when I connect it to this line and this line, it becomes the letter A. Conversely, if I were illiterate, maybe I’d think the same shape was a pencil tip, or the point of an arrow. I, a tower. U, a cup. I am fascinated by the idea of asemic writing – purely visual, devoid of any language or specific meaning, yet mimicking the quality of writing, the sense of grammar, sequence and flow. It is a hybrid craft, sitting somewhere between abstract art, graphic design and written communication. Like a piece of experimental instrumental music, it is open to interpretation, and the text becomes a mirror. What do you see?

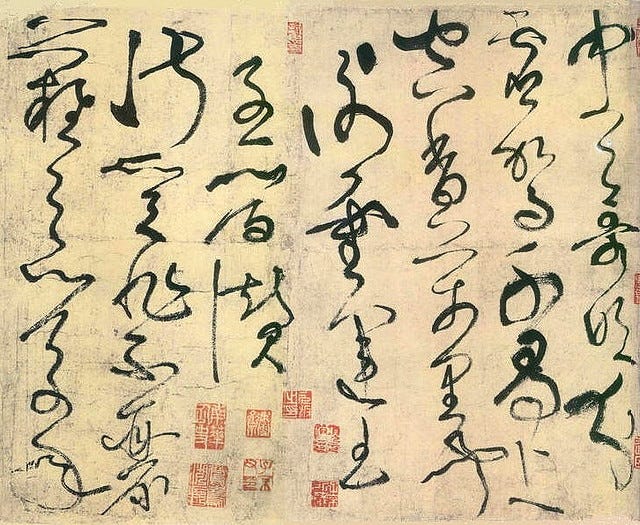

Asemic writing has roots in some of the earliest forms of writing, and is heavily influenced by Chinese and Japanese calligraphy – an art form in which text and painting naturally converge. In the 8th century, the calligrapher and poet Zhang Xu (aka “Crazy Zhang”) became famous for his proto-asemic script. According to legend, whenever he was drunk, he’d pick up his brush and create explosive illegible texts, mad lines of ink unfurling like snakes down the page. He’d be amazed at them when he woke up the next morning, but unable to replicate them sober.

Today, asemic writing is closely associated with avant-garde art movements, especially Surrealism. I particularly like Man Ray’s Space Writing (1935), which fuses self-portraiture, light and text, using long exposure and a light pen to draw illegible patterns in the air. The artist himself appears as a dark figure in the background – a shadow – while the text shines with a spectral, dreamlike intensity. At the centre of these illegible scrawlings, his signature hides in plain sight. It’s a short step away from automatic writing – the visual equivalent of speaking in tongues. Often associated with “spirit writing”, the Surrealists were equally interested in utilising this experimental technique to tap into dormant creative forces.

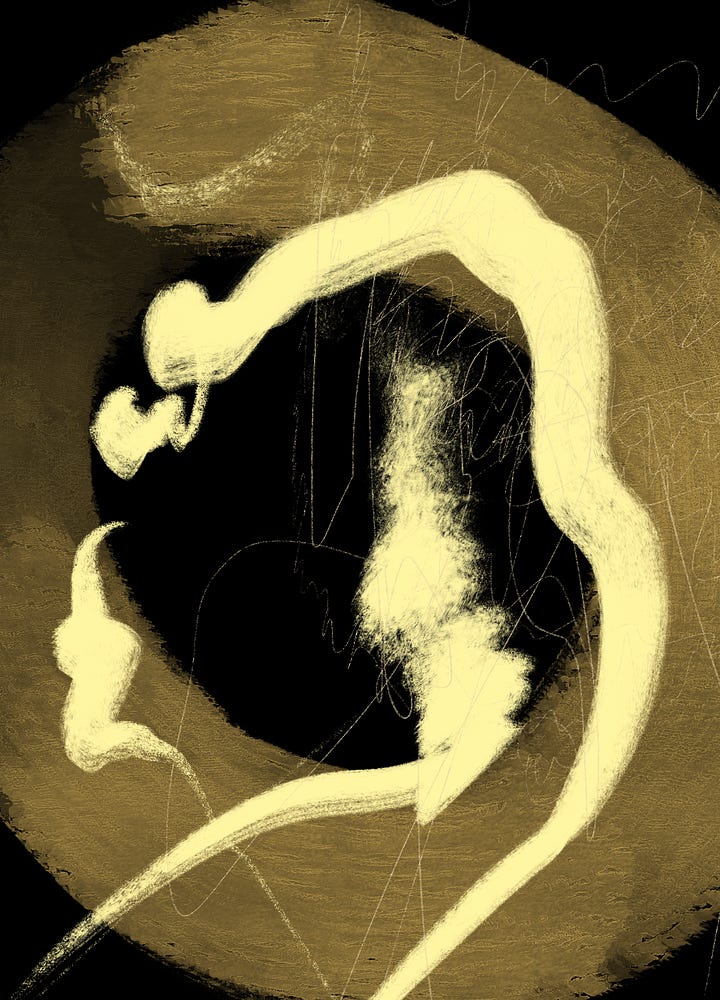

Later, sitting on the bed in my hotel room, I attempt something to bring me closer to that experience on the beach. On my iPad, I open a black canvas and select a calligraphy pen setting, choosing the colour of lightning (impossible, so I settle for a light gold colour). Then I switch off the lights and blindfold myself. Darkness again. I try to relax, letting my hand move freely and loosely across the screen. The key to this exercise is in letting go, surrendering control over the process – something I am not very good at. I can’t stop myself from peeking. A lot of my satisfaction in the act of writing comes from the way my words look on the page – ink on paper, neat black characters on a white screen. It is not thought of as a visual art, and yet it is – a word is, quite literally, an image. Writing in the dark changes the process. You cannot obsess over the way things look, and the physicality of the act becomes more apparent. I find myself thinking that I am making the line dance, getting a feel for the motion of the pen. I notice the sound – a clinical tap tap tap – and find myself wanting something more real. A hard brush scraping the canvas. The wetness of real ink. The ability to splatter and spill in a more fluid way. There’s only so much you can do with a plastic pen and a screen. It takes some patience, but eventually, some essence of the memory surfaces and spills out on the page.

All artists and writers deal with the question of representation. But how close to the truth can we ever get? When René Magritte painted the words Ceci n’est pas une pipe under the image of a pipe, what he was trying to show us was the distance between language, images and reality. In other words, “the treachery of images”. A map is not a territory; a word is not the thing it describes. In the same way, I can’t be sure that my account of the lightning on the beach is all that truthful. By rendering it in language, I have distorted it, carved it into a shape that pleases me.

In the act of representation, we claim ownership over something – it could be an experience, a landscape, or even a person – and transform it according to our own image of the world. Maggie Nelson writes in Bluets, “Admit that you have stood in front of a little pile of powdered ultramarine pigment and felt a stinging desire… You might want to reach out and disturb the pile of pigment, first staining your fingers with it, then staining the world… But still you wouldn’t be accessing the blue of it. Not exactly.”

To stain the world with a colour – I love that image. It speaks of the instinct that drives us to make our mark on the world, whether it’s through writing or art. A signature in blue that says “I was here”. But as beautiful as it is, the truth of the thing we are trying to represent is always beyond reach. It is too complex, too ineffable, to fit neatly in the story we are trying to tell. We know this, but still, we peer into the darkness, making up wild tales about what is – and isn’t – there.

Nature can certainly disrupt the senses. We had a similar experience with the total eclipse in Cornwall- eerie, spiritual but weirdly communal with fellow observers. The silence of the birds was surreal but their joyful chirruping as the sun was exposed was like a reawakening. I feel your storm felt like a cleansing and a new beginning. Enjoy these momentous travels!