In the summer of 2022, I bought myself an Olympus OM-10 from an online shop that refurbished vintage cameras. Having grown up in a digital age, the idea of going analogue felt romantic. There was something thrilling about its weight, its cool metal body – a proper piece of machinery. Like many of my favourite things, it felt arcane, offering no easy answers, no shortcuts and no reassurance I was on the right track. How to use this thing – and how to actually get good pictures out of it – was a mystery I would have to slowly unravel – which, in our age of instant gratification, made it all the more exciting.

That year, I was taken by the idea of documenting my own history. I had reached the mystical age of 27, and good things had happened. To borrow the iconography of the Tarot, it was a year in which the Wheel of Fortune spun freely, hurtling optimistically from one major life change to another. The result of this was that for the first time in my life, I could imagine a more concrete future. And if I was to glide into the future I imagined, I needed a past to take with me – a history that fitted the narrative I wanted to build.

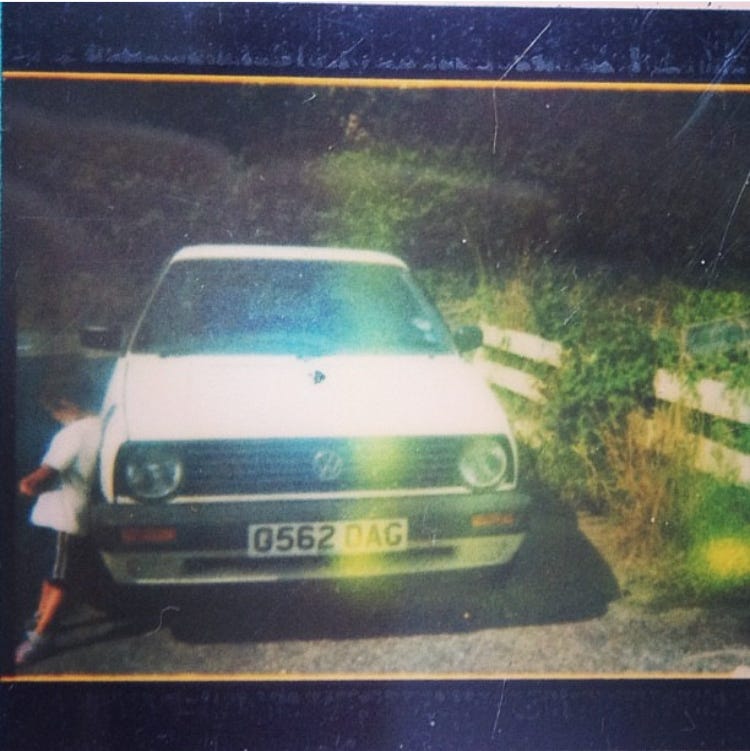

When I was a child, I was given a polaroid camera. It might have been a birthday gift, or a Christmas gift – I don’t remember. Its tiny photos were printed instantly on little squares, fringed with metallic pink and blue strips that were patterned with spaceships, spirals and hearts. You could peel off the back to turn it into a sticker – it was great fun. Well over two decades on, we keep finding these little mementos scattered around my parents’ house – under the bed, behind the sofa, hidden between old books. Evidence of childhood: a toad in the palm of my father’s hand; my brother leaning against an old car, long gone; soft toys lined up in the style of a school photo. There is nothing especially profound about them, but these pictures reveal what was important to me at the time – life through the lens of a six-year-old. The actual memories are hazy, if not gone altogether. So I play the detective, putting together a picture of a child lost in time.

The sort of photos I love most are direct and intimate. They are a way of observing and making sense of the world around me, almost like diary entries. What I love about film is that slightly gauzy quality, its layers and texture, its capacity for ambiguity – qualities which mimic our own memories, to some extent. The image itself feels like a physical thing, bruised by light, scratched by the reel, acquiring scars through the process of becoming. It takes on its own voice, asks us to listen.

Every photograph is a historical record. When we look at it, we live again through that moment – but how does the picture affect how we remember things, and consequently, how we perceive reality? The question makes me think of colourisation – the act of restoring true-to-life colour to historical photographs. As artist Stuart Humphryes says, “We know that these people and places existed – the evidence is there in front of our eyes – but somehow, they seem less real; mere ghostly faces from a time and place long since vanished. These are people with different values, different fashion and different lifestyles than us. We cannot fully understand them because we don’t fully see them as they were in reality.”

But with the restoration of colour, and the smoothing and sharpening of pixels, an old photograph is brought into high definition. There is a strange effect where the temporal distance closes. The past brushes up to the present; we can imagine being there, what that person might have been like. We can empathise with them, because we are part of the same plane of reality. Life flickers into colour.

Conversely, the use of old technology creates a sense of distance. We estrange ourselves from the present. The texture of time itself has taken on a rawer, grainier quality, and the visual memory exists some place in between. It seems we are only capable of believing what we see before our eyes.

Recently, watching the sun break over the temples of Angkor, I was struck by how many people – including myself – are unable to look at something beautiful without instantly reaching for the camera. It is as if we don’t trust ourselves, that we need some kind of eye-glass to see things as they truly are, or as we want them to be. Like a modern-day Claude glass, softening life into painterly tones. As our technology advances, moving into some strange hybrid of real and artificial forms, are we peering into different versions of reality?

Which reality do we choose to believe in? There are so many – representations of representations, shimmering like reflections across the surface of a pond (what else is a meme, after all?). Most reflections shift with the light, dissolve into nothing. But some images sear into our mind and can change our whole perspective – about ourselves and others, and the stories we tell ourselves.

Last September, we visited Bordeaux. There’s a photograph of Nathaniel, taken as we sat down for lunch at a seafood restaurant. He is in full wine-person mode, thoughtfully swilling a glass of white wine – a 2022 Pessac-Léognan from Château Tour Léognan. Half a dozen oysters lie on the table, the light pooling around them. Everything about this photo looks delicious to me: the cold white wine, glass slightly frosted; the silky oysters and sliver of lemon; the assertive red of Nathaniel’s shirt.

In retrospect, it is a perfect wine memory. We had spent the morning wandering around the city as it slowly woke up, exploring the market, dipping into boutiques and bookshops. By the time we sat down for lunch, we were starving. The oysters were plump and juicy. The fish and vegetables that came moments later were soft and delicious. The wine was just so refreshing, with an unexpected ripeness coming through, all lemons, orchard fruits and nectarine. It was just right for the occasion, no intellectualising needed.

I can still grasp these flavours in my mind, and I think some of that comes down to the richness of this image. I want to eat it all again, drink it all in, lose myself in the whole moment. Never mind the fact that, in reality, we were so stressed about the possibility of being evicted from our flat that I hardly slept and we spent the whole trip worrying. When I look at my photos from that trip, I see none of that anxiety. I see delicious food and wine, a scene painted in glorious late summer light – somewhere I want to be again. The image is a holiday from reality, but it is what will endure.

I believe it was Anaïs Nin who declared, “We write to taste life twice”. I think the same can be said of photography. We are often incapable of tasting things in their fullness, with the luxury of time, when we are wrapped up in the moment. And so we look to whatever images we have as evidence – that we did indeed experience these moments, that those things actually happened to us – perhaps to feel our way back into remembering things. To build a picture of our own histories, to have something to show for it all. Truth is something else altogether.

On the subject of looking…

‘Look-A-Here’ by Ramsey Lewis Trio, 1963

The other night, we were sitting on the balcony of Laundry Bar in Siem Reap, drinking Cambodian beer, pastis and smoky whisky. Jingjok lizards scuttled across the walls, flicking their tails, while people played darts and pool in the background. The playlist was excellent, but this song really made us sit up and listen closer. What a tune – a perfect song for a hot, lazy night. I adore Ramsey Lewis’ infectiously catchy jazz piano, simultaneously smooth and snappy. His music is loose, in no rush whatsoever, but sharp, building in intensity and never losing focus. That languid piano, that skulking bass. Like blowing perfectly formed smoke rings and watching them shimmer and dissolve in the air. Enjoy with your own choice of random drinks – anything goes.

Lovely pictures, Issariya- definitely capturing mood and atmosphere. The stills allow the memory to recreate the moving film reel of the history. One advantage of the instant smart phone though, the capturing of voices. I'd love to have my children's sweet sounds on record, lisping out new words when they were forging language; I enjoy my grandchildren's squeaks so much! We do have the French oral GCSE tapes- Je me couche....😻! So happy to see you both so relaxed, too.