I’m a terrible sleeper. Following the insomnia rulebook (don’t look at your phone, don’t look at the time), I’ve revived an old iPod from over a decade ago, set it on a random time zone and loaded it with classical music tracks to listen to in bed. I’m no traditionalist, but I love classical music – the one remaining legacy of 13 years of music lessons. I find it the perfect balm when my ears are craving something but I don’t want to think too much about it. I want to be soothed, transported, lulled to sleep. To have the lights softly, sweetly knocked out of me.

One of my favourites is Scheherazade, a symphonic suite by Rimsky-Korsakov based on the story of One Thousand and One Nights. It is everything I want to ease me into my dreams: soft, romantic passages suggestive of the sea, swelling and expanding, building in drama and narrative. Soon, I am far from South London, far from my thin, cracked walls and the rumbling snores of my neighbour. I’m transported to a hot Arabian night, listening to clever Scheherazade beguiling her husband, the Sultan, with absorbing tales of princesses, sailors and genies. My eyelids grow heavy, and I’m finally slipping into that dreamspace. Then, someone coughs.

It takes me a moment to realise that this cougher is not in the room with me, and it is not one of the neighbours. It is someone inside the track. With a jolt, I’m reminded that what I’m listening to is a real-life concert, attended by real-life people. People who might just go and do something like cough. The world is suddenly bigger than this track – and all the layers of stories within it – had initially suggested. I will never know who these people are, but their memory is unwittingly preserved in this record.

What I’m listening to is a representation of an event that has happened, a living moment that will never recur. I will never know how the conductor’s arms move, as they bring in each new fragment of music. I will never know how the lead violinist leans into the music, receives it, translates it with each movement of the bow, or how their polished shoes might catch the light. The cougher has this advantage over me – let’s call it historical privilege – and I almost resent them for it.

The music itself is born of a series of records. One Thousand and One Nights is a vast, sprawling body of Middle Eastern folktales, collected over the course of centuries. The roots of these stories stretch back to ancient Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit and Mesopotamian sources. Like all folktales, there are so many different versions, each retelling embellishing and building on the last. Each collection contains different stories, perhaps reflecting the preferences of their storytellers. Tales are embedded within tales, records within records.

When we make a record of something, we’re translating the essence of that thing into a language that can be understood by others. Stories and music expand on universal emotions. They are forms of representation, requiring a translator to reach into the shadowy realm of ideas and bring home something we can understand.

Our understanding of wine is built on records too. What is the tasting note but a representation of how a wine is exhibiting at a particular moment in time? This act of recording is born of the same motivations that might compel someone to record a concert: so that the thing can be enjoyed and understood by others. Just as music is written onto a score, wine is translated into notation.

It seems like an impossible act of ventriloquism, that literal language can express the essence of wine in all its complexity. The combination of grape, soil, climate, terrain, season, winemaker’s vision. How much rain fell in spring, the mild summer winds. How much oak was used in the winery. Where the tree grew, how much rain fell on it, how it swayed in the breeze. Wine is a symphony of the earth, brought to life by an unfathomably vast orchestra under the direction of the winemaker.

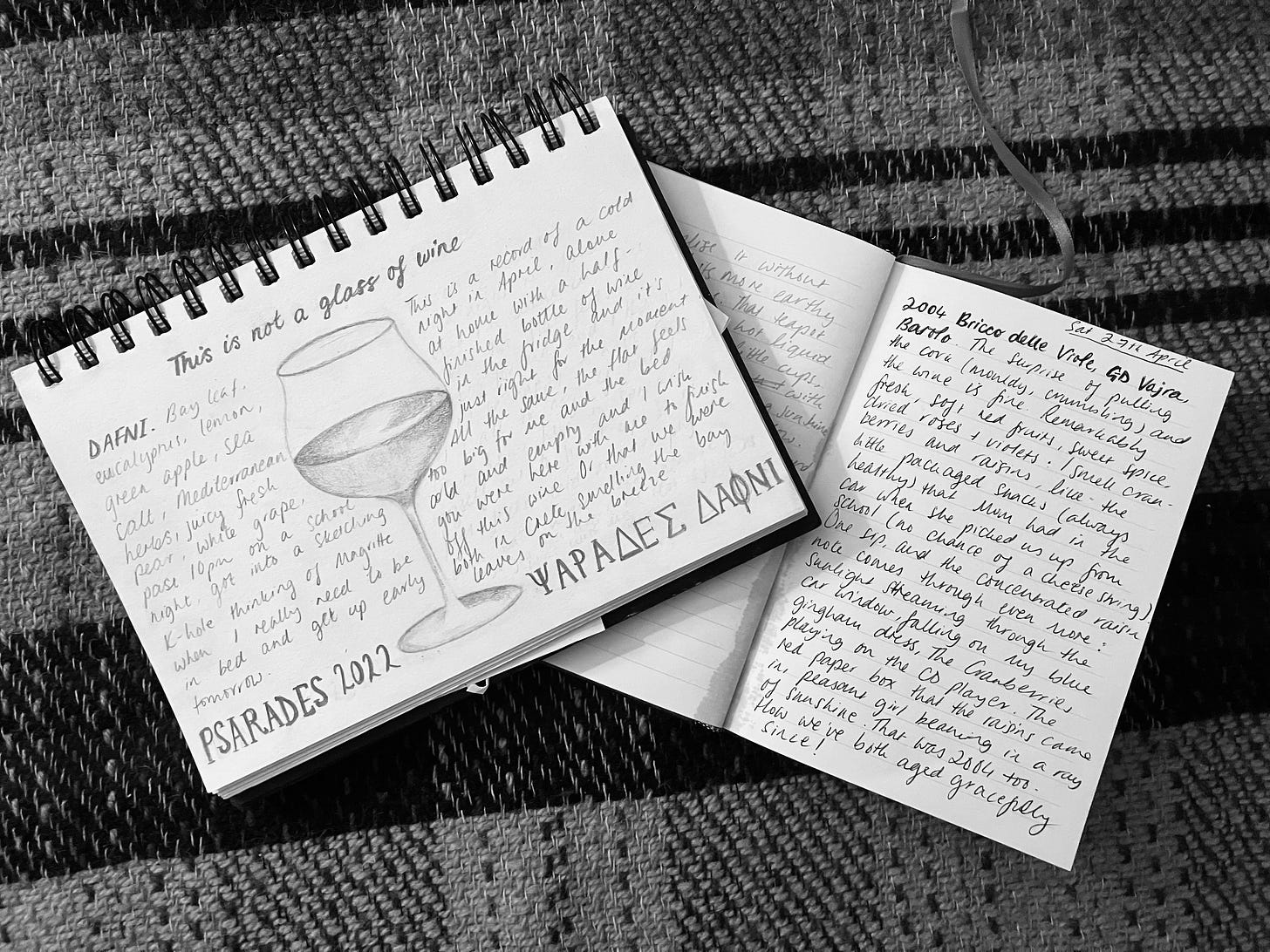

So how do you go about writing a tasting note that expresses a wine in its full complexity, yet is easily understood – even compelling – to others? It is more thoughtful a task than people realise – and yet, in the wine trade, it is often treated as a tedium, perhaps even an afterthought. I have written plenty of tasting notes. Whether they are any good or not, I don’t know. More often than not, they are quickly scrawled, splattered with wine, favourites circled and starred. They do not adhere to the systematic approach you learn with the WSET, which I happily disregarded as soon as I passed my exams. They are unabashedly a product of my personal tastes and memories, so they’re inherently imperfect. But the more I write, the more I find myself thinking about the tasting note as a form of expression. What are the mandatories, and where do the liberties lie?

What constitutes a good tasting note at all? Is its purpose to represent the elements of the wine as accurately as possible, like a medical photograph? Or, like a liberal translation, is it more of a poetic exercise – an attempt to capture the imagination? What are the political dimensions of tasting notes? How might we use it as an opportunity to amplify our voices, assert our presence, shift the dial?

Treating a tasting note as an avatar for the wine itself presents inevitable limitations; the liquid will always be different things to different people. Instead, it might be more generous to think of it as a record of a living moment, shaped by the sensation of taste. You will never be the same again, and nor will this wine. What happens in these precious few moments that you spend together?

Like Scheherazade, we are each storytellers putting our own twist on the tale. To quote a certain noughties pop star, the rest is still unwritten.

I completely relate to this essay! I have had insomnia my whole life. And I have tried to lull myself to sleep with classical music and find myself jolted awake at older recordings of live performances that don’t mute the audience noise. I think you present some really thoughtful concepts here, regarding wine tasting as an in-the-moment point of view. Lots to consider!

I was thinking as I was reading, how can we listen to the voice of the wine? And if we savour and listen to great accompanied musical storytelling, do we grant the wine agency to voice its own lifecycle and surprise us in unexpected ways?